by Peter Barclay

When Hurricane Harvey struck Texas and Louisiana in 2017, the world saw the dramatic images: submerged neighbourhoods, families rescued by boat, hospitals scrambling to stay open. What we didn’t see—what we rarely see—are the long shadows disasters cast long after the floodwaters recede.

A new University of Michigan study has illuminated one of those shadows. Older adults exposed to heavy rainfall during Harvey faced a 3% increase in the risk of death over the following year. Not in the days after the storm. Not in the chaotic weeks of cleanup. But across twelve quiet, untelevised months.

The research is a reminder that climate‑driven extreme weather is not just an environmental issue. It is a health issue, a systems issue, and a human‑vulnerability issue. And its consequences accumulate in ways that are both predictable and preventable.

Lead author Sue Anne Bell, an associate professor of nursing at the University of Michigan, puts it plainly: disasters don’t just break things—they expose what was already fragile.

Routine dependent

Older adults, especially those managing chronic conditions, depend on routine. Routine dialysis. Routine medication refills. Routine check‑ins with caregivers. Routine access to electricity, refrigeration, transport, and communication. When a storm interrupts these routines, even briefly, the effects ripple outward.

Bell’s team analysed Medicare claims for nearly 1.8 million adults aged 65+ across Texas and Louisiana. They paired this with historical rainfall data to understand who was most affected and why. Their findings are sobering:

- People with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias experienced a 5% higher risk of death, with an estimated 1,245 additional deaths in the year after Harvey.

- Chronic kidney disease patients saw a 4% higher risk, with 423 attributable deaths.

- People with diabetes also faced a 4% increased risk.

- Black and Hispanic/Latino older adults experienced 6% and 13% higher mortality risks, respectively—an unmistakable sign of structural inequity.

These are not small numbers. They are not short‑term spikes. They are the quiet, cumulative consequences of disrupted care, lost access, and systems stretched beyond their limits.

And they tell us something important: the official death toll of 103 dramatically underestimated the storm’s true human cost. Bell’s team estimates that 3,738 additional deaths among older adults can be linked to the year following Harvey.

Why this matters

In 2023 alone, the United States experienced 28 separate weather and climate disasters, costing nearly $93 billion and claiming 492 reported lives. But as this study shows, the real toll is almost certainly higher—and it is disproportionately borne by those already living with chronic disease, limited mobility, or reduced access to care.

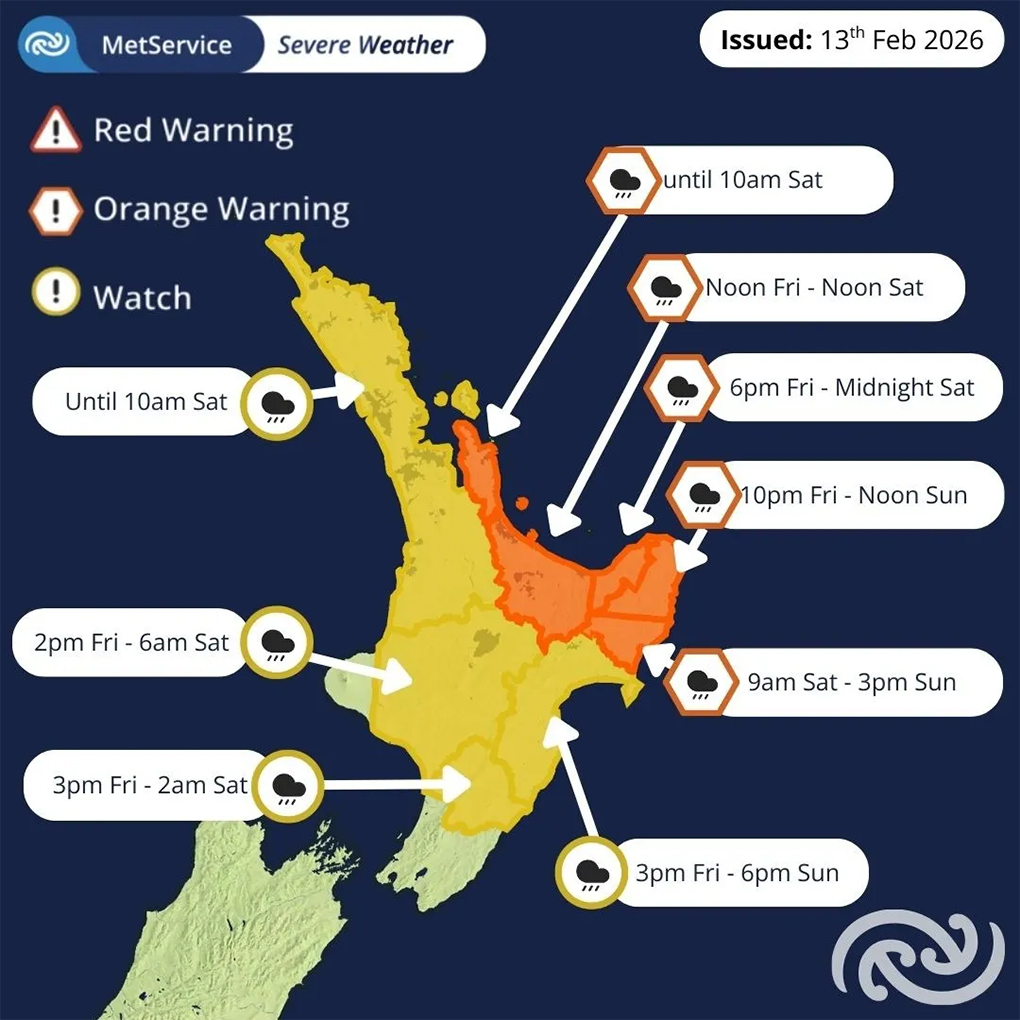

For countries like New Zealand, where climate‑driven storms and flooding are becoming more frequent, the implications are clear. Severe weather is not a one‑day event. It is a long‑term health stressor.

And for Whole Food Living, which champions prevention, resilience, and systems‑level thinking, this research lands squarely in our wheelhouse.

What stands out most in Bell’s findings is not just the numbers—it’s the pattern. The people most affected were those who:

- required regular, ongoing medical care,

- lived with cognitive or mobility challenges,

- or belonged to historically marginalised communities.

In other words, the storm didn’t create vulnerability. It revealed it.

This aligns with what we see in nutrition, chronic disease, and environmental health. More broadly, the same communities that face the greatest barriers to healthy food, stable housing, and preventive care are also the least protected when disaster strikes.

Climate change is not an equal‑opportunity disruptor. It amplifies existing inequities.

A prevention-first lens

If disasters magnify fragility, then prevention must strengthen resilience. That means:

- Health systems designed for continuity, not just crisis response.

- Community‑level preparedness that prioritises older adults and those with chronic conditions.

- Policies that address inequity, not just infrastructure.

- Lifestyle and nutrition strategies that reduce chronic disease burden long before storms hit.

Whole Food Living has long argued that prevention is not a luxury—it is a necessity. This study reinforces that message. A healthier population is a more resilient population. A connected community is a safer community. And a society that invests in prevention is one that weathers storms—literal and metaphorical—far better.

The most powerful insight from this research is also the simplest: the end of a disaster is not the end of its impact.

For older adults, especially those managing chronic disease, the danger doesn’t disappear when the rain stops. It lingers in missed appointments, delayed treatments, disrupted routines, and the slow erosion of stability.

As climate change accelerates, we must widen our lens. The true cost of severe weather is not measured only in flooded homes or broken roads. It is measured in long‑term health, in resilience, and in the lives quietly altered long after the headlines fade.