by Peter Barclay

The ultra-processed food debate took an interesting, if unexpected turn in the US this week. Unexpected because of the quarter it came from, and interesting because it’s put a new slant on what ultra-processed foods actually are and perhaps questions whether they need a definition at all.

A precursor to last week’s surprise happened on July 23 with a combined press release from the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA and USDA, which, because of the MAHA initiative, “now seeks to address the health risks of ultra-processed foods.”

“The agencies are announcing a joint Request for Information (RFI) to gather information and data to help establish a federally recognised uniform definition for ultra-processed foods—a critical step in providing increased transparency to consumers about the foods they eat,” the release said.

“Ultra-processed foods are driving our chronic disease epidemic,” said HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. “We must act boldly to eliminate the root causes of chronic illness and improve the health of our food supply. Defining ultra-processed foods with a clear, uniform standard will empower us even more to Make America Healthy Again.”

It’s a statement that is surely encouraging, especially in sleepy hollows like New Zealand and Australia, where the UPF issue is certainly debated amongst academics and some health officials, but is far from gaining real political traction.

A worldwide cold

And considering the commonly quoted expression “when America sneezes, the world catches a cold”, would we be naïve in thinking that the outcome of the coming upheaval could be a dose of good health?

Before I get into the big surprise, it’s crucial to understand why the UPF debate hits so close to home for those of us in the whole food plant-based (WFPB) community. This isn’t just an abstract argument — it’s an issue that affects two diverse camps almost equally. Both meat eaters and plant-based consumers often end up reaching for the same types of products.

The fact is, whether you consume animal products or strictly follow the WFPB mantra, it’s nearly impossible to become UPF-free, unless, perhaps, you make all your meals at home. For a visual explainer on this, take a look at the following product images and consider their captions.

UPFs a major issue

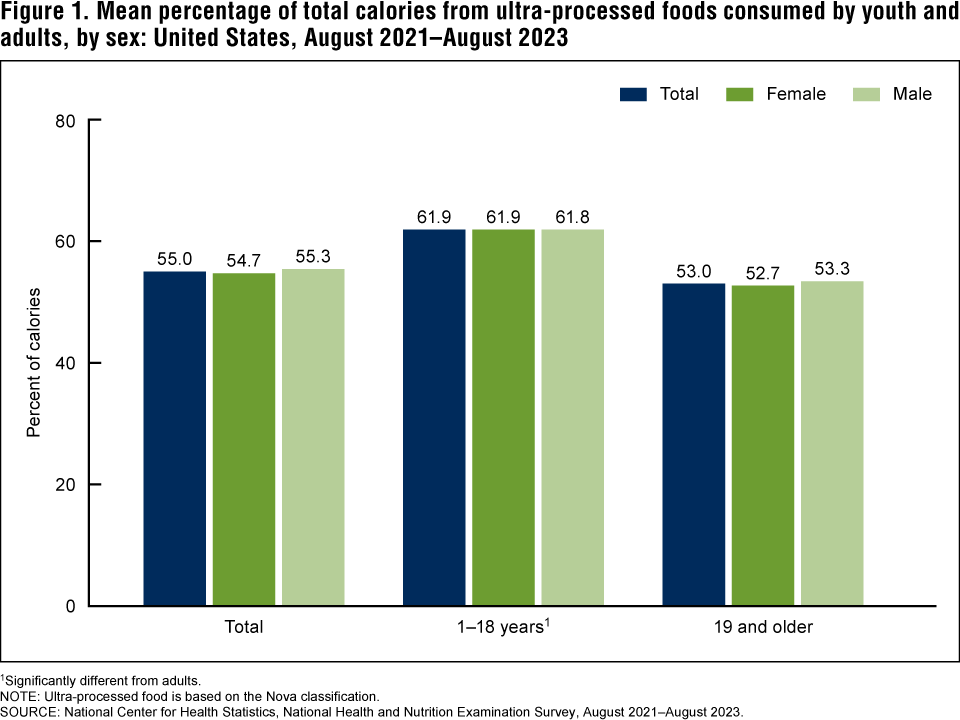

There is little doubt now (unless you’re a manufacturing food producer) that UPFs are a serious issue and, dare I say it, Vegans and meat lovers have found some common ground here. And we consume a lot of them, as the table below shows.

The key findings from the NCHS data briefing completed last August are:

- During August 2021–August 2023, the mean percentage of total calories consumed from ultra-processed foods among those age 1 year and older was 55.0%.

- Youth ages 1–18 years consumed a higher percentage of calories from ultra-processed foods (61.9%) than adults age 19 and older (53.0%).

- Among adults, the mean percentage of total calories consumed from ultra-processed foods was lowest in the highest family income group.

- Sandwiches (including burgers), sweet bakery products, savory snacks, and sweetened beverages were four of the top five sources of calories from ultra-processed foods among youth and adults.

- Between 2013–2014 and August 2021–August 2023, the consumption of mean calories from ultra-processed foods among adults decreased.

Citizen petition filed

The real kicker, however, came around mid-last week when Dr David A. Kessler, a former head of the Food and Drug Administration, came up with a path to take on the food industry. Kessler, who is also a lawyer, led the charge against tobacco companies in the 1990s, filed a Citizen Petition that must be answered in 180 days.

It’s something of an ironic twist that Kessler, who is not typically considered best mates with RFK due to their opposing views on vaccines, has seemingly devised a way to power him forward – if Trump agrees.

Kessler’s point is that the FDA already has the authority and the scientific evidence to declare that some of the core ingredients in ultraprocessed foods are no longer “generally recognised as safe” or G.R.A.S. for short.

Some say Dr Kessler’s strategy is a silver bullet, because it does not require the Food and Drug Administration to determine that the ingredients are unsafe — only that their safety is in doubt. And, there’s an even more interesting twist at play here – it would also put the onus on manufacturers to prove their ingredients aren’t harmful.

“This is the great public health challenge facing us,” Kessler told the New York Times. “Twenty-five per cent of American men are going to develop heart failure. Thirty to 40 per cent of us are going to be diabetic. Twenty-five per cent of us are going to have a stroke.

“And the primary driver of that,” he added, “is our diet and what we are eating.”

Nutritionist Marion Nestle says the Kessler solution would cover an extraordinary amount of food, but the bottom-line question here has got to be: Is MAHA up for the fight?

Meanwhile, back in New Zealand, lobby group Health Coalition Aotearoa is about to open the doors on its Healthy Futures Summit – an intense nine-hour deep dive into the future of health in New Zealand and what can be done about it.

One of the many topics to be discussed, and perhaps the most relevant as far as this article is concerned, is titled: Selling Sickness: How Junk Food Became Normalised. The opening address, by Australia’s Professor Gary Sacks, will cover “addressing excessive corporate power and incentivising corporate models for health.”

In New Zealand and Australia, the primary brake on food ingredients is in the hands of Food Standards Australia New Zealand, which, for 25 years now, has set requirements across both countries.

If the US coughs and bellows big time over food ingredients, the outcome will likely affect what can be included in Dowunder products destined for the American market. Health outcomes, like tariffs, are a worldwide wind.