Health care systems worldwide are coming under unprecedented pressure. Ageing populations, increasing rates of chronic disease, advances in expensive medical technology, and growing public expectations mean that costs are rising faster than economic growth in many countries.

Whole Food Living has long maintained that without decisive action, the gap between what is needed and what governments can afford will rapidly widen. Without severe cuts in politically unpalatable directions, the future cost trajectory is not sustainable.

The most effective way to address this challenge is to shift the focus from treatment to prevention. A prevention-first health strategy would recognise that the most significant long-term gains in both health outcomes and economic sustainability are achieved when illness is avoided in the first place.

These points were canvased in detail by New Zealand’s previous Health Minister, Dr Ayesha Verrall, economist Shamubeel Eaqub, with several other speakers at this week’s Healthy Futures Summit in Auckland. Health Coalition Aotearoa organised the summit with sponsorship from the New Zealand Heart Foundation.

Broadly, they explained that placing prevention at the heart of policy is not simply a matter of encouraging individuals to “live healthier.” It requires comprehensive strategies that address the broader determinants of health: safe and healthy environments, equitable access to nutritious food, opportunities for physical activity, robust mental health support, reduced exposure to harmful substances, and strong public health education. It also involves targeted screening and early detection programmes that can significantly reduce the cost and complexity of treatment should disease occur.

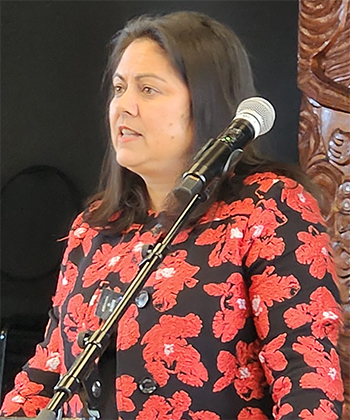

Dr Ayesha Verrall

Dr Verrall is a current New Zealand politician and former Minister of Health under the last Labour Government. Before entering Parliament, she was an infectious-diseases physician and researcher with expertise in tuberculosis and international health. She graduated from the Dunedin School of Medicine in 2004 and trained in New Zealand and Singapore. Since 2020, she has been a Member of the New Zealand House of Representatives for the Labour Party.

Dr Verrall is working on a pathway to make it happen.

“First, we need to make the case for prevention in ways that make sense to people’s everyday experience, so they understand its importance in policy,” she told the audience.

“We need to make sure people understand that the reason the emergency department is crowded is because primary care is under-resourced. That the reason they can’t get a hip replacement is because we have not confronted our unhealthy communities or taken action on obesity. The reason we can’t guarantee timely care for a heart attack is because more people are ending up sicker and putting pressure on our hospitals.”

She said when she visited communities around the country, people understood these examples, “but we need to engrain them in our thinking about health. It’s clear people are worried about the state of the health system. Our polling shows it’s among people’s top two concerns, closely behind the cost of living.”

She said the second critical factor that needed to be recognised was that it wouldn’t be possible to develop “a prevention-focused health system” without strong general practice.

“Successful general practice and wider primary care networks are necessary for achieving that vision. It means small issues get dealt with early – before they require costly hospital treatments.”

She acknowledged there were other ways of achieving prevention, but “everyone must have access to medical care … “and right now, a visit to the doctor is climbing out of reach.”

Health will probably always remain a political football, but right now, in New Zealand especially, it sits within a perfect storm of confused political ideology and very real personal need.

It came, she said, as power, food, transport and housing costs were skyrocketing for families, and left more people putting off trips to the doctor. Thousands of people have lost jobs and been left struggling to find work.

“I’m not convinced that we have the right options on the table with respect to healthy food. The Public Health Advisory Committee report recommends efforts to improve food composition but does not offer a clear pathway to doing so. I haven’t found credible proposals about how we achieve those changes through New Zealand’s joint food system with Australia.”

On a broader note, she referenced the smoke-free legislation that the current Government had now repealed. “Different ways” needed to be considered here.

“One proposal we (Labour) didn’t consider in government was an import ban, and I do think that is worth entertaining seriously,” she said.

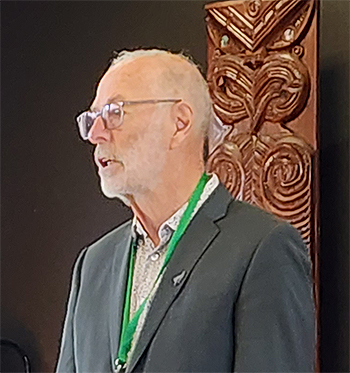

Shamubeel Eaqub

New Zealand-based economist, author, and media commentator Shamubeel Eaqub is known for his incisive and easily understood analysis of economic and housing issues. Born in Bangladesh and raised in New Zealand, he has worked in banking and consultancy. Eaqub frequently appears in media, writes books on economic inequality, and advocates for evidence-based policies to improve social and economic wellbeing.

The most significant factor in all this boils down to what type of political persuasion gains the axis of power. For Shamubeel Eaqub, the situation here is clear.

In response to a question from the floor regarding a sugar tax being introduced by a right-leaning government in Britain, he said: “There, I think, because it was a right-leaning government that was willing to bring it in, it was easy for the left-wing government to keep it because they agreed with it, but I don’t see that happening in New Zealand where a right-leaning government is going to bring in a sugar tax.

“I would encourage us to focus our energy on the kind of policies that would last through the political cycle, because the reality is we don’t have time and energy to do things that will only last three years. I think amongst the more affluent people of New Zealand, ‘it’s you’re fault’ for drinking those sugary things. You are responsible, so you should take responsibility.”

Finally, and in reference to the now general acceptance that smoking is unhealthy, Eaqub says it took time for lasting policies to embed. It didn’t happen without support from both sides of the political spectrum.

While he’s not above making bold statements, between the lines, his message is more about reading the room.

“I think slow is good,” he said.

Critically, a prevention-first policy provides a clear “line in the sand” for health authorities — a shared vision around which priorities, targets, and funding decisions can be coordinated.

It creates a framework where every sector, from education and transport to urban planning and taxation, is seen as part of the health system. For example, ensuring walkable cities, regulating unhealthy food marketing, and incentivising smoke-free environments become essential health interventions, not peripheral considerations.

For the public, such a strategy sends a powerful message: health care is a shared responsibility. By making the long‑term economic realities clear — that without prevention, future services may be rationed or unaffordable — governments can foster a sense of urgency and participation.

Awareness campaigns, combined with accessible tools and community programmes, can help people understand how their choices today directly impact not only their future wellbeing, but also the sustainability of a system too many of us take for granted.

Mayoral Opening

Auckland Mayor Wayne Brown opened the conference. A former District Health Board chairman, he has first-hand knowledge of the health sector. I appreciate the scale of the challenge, he said. “Everything Auckland Council does has an impact on the community. Plenty of research suggests that urban sprawl leads to bad health outcomes. There’s a lot we can do to ensure that our planning processes enhance the quality and opportunities to live healthy and well-connected lives.”